Donald Trump has changed the way scientists engage with presidential elections.

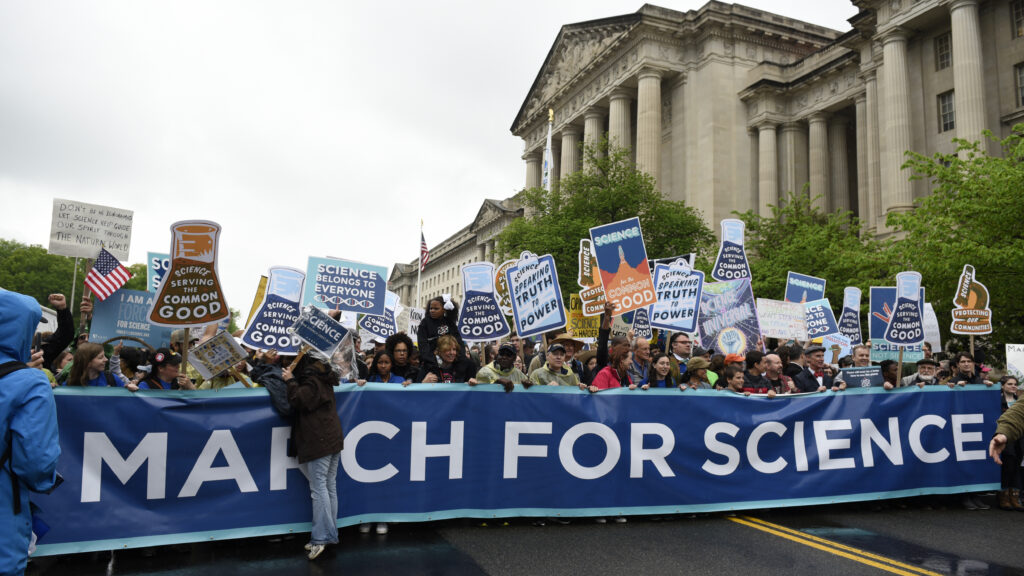

After being voted president in 2016, tens of thousands participated in the March for Science across the country the following year. When he was running for re-election against Joe Biden in 2020, several journals, including Nature and The Lancet Oncology, took the historic step of endorsing a candidate in a presidential race for the first time.

This fall, scientists and scientific journals are facing a new reality. Covid-19 is no longer a major election issue and Americans’ trust in science has declined since 2020.

STAT asked the editors and contributors of a variety of science journals about the thinking behind their approaches to the election and spoke with science communication experts about the role of science in politics today. A core concern became clear: While the outcome of the election will have major ramifications for health issues such as abortion, the opioid epidemic, and global health policy, people in the field are increasingly concerned about how partisan politics might further erode faith in science. the institutions.

“We have a lot of really difficult social conversations ahead of us,” said Dietram Scheufele, a communication scientist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “Coming into the room as a perceived partisan player for those conversations will be absolutely detrimental to evidence-based policymaking down the road.”

To approve or not to approve

In October, the journal Science published a special issue on democracy that included news and an editorial about the US election. Science decided not to endorse either candidate because of its status as a non-profit organization, which prohibits it from getting involved in campaigns. Science editor-in-chief Holden Thorp also said the journal could have more impact in other ways.

“We think the facts are so clear on this sort of thing that our readers can easily glean from what we report and comment on everything they need to make up their own mind,” he said. “We don’t think we would add anything to that by making an endorsement.”

One popular journal that chose to make an endorsement was Nature, which published an editorial headlined: “The world needs a US president who respects evidence.” This is the second time the magazine has chosen to endorse a US presidential election.

“The fate of scientific research, evidence-based lawmaking and government receptivity to independent science-policy advice will be key determinants of the country’s future course and long-term well-being,” the journal wrote in its endorsement this week.

The approval of Nature 2020 was controversial. The journal Nature Human Behavior later published a study on the decision that found that when Trump supporters were told about the endorsement, they trusted the journal less, were less likely to read Nature articles on Covid-19 and had less faith in science in general.

Scheufele raised a particular concern about Nature’s choice to approve.

“To what extent a British magazine owned by a German publishing house telling Americans who to vote for is a particularly good strategic idea is a question I think is open to debate,” he said.

Nature declined to answer questions about its decision to adopt.

It’s also worth noting that Scientific American, a magazine that covers science for a popular audience and is owned by Springer Nature, decided to endorse Kamala Harris in this election — a decision that opened her up to both praise and criticism. “We have a lot of knowledge and we have, I think, the opportunity and the responsibility to explain how the science is at stake in the election,” editor-in-chief Laura Helmuth said on STAT’s First Opinion Podcast. “And not just science, of course — health care, the environment, education, technology.”

JAMA and its network journals did not make an endorsement, instead choosing to publish 111 articles about the election and various policies on the ballot along with an editorial summarizing the results. The papers focused on four areas: prescription drug costs, women’s health, public health policy, and the opioid epidemic.

“We’re not trying to take a position or make an endorsement, but we’re really just trying to really highlight the high risks to health and health care in this and any election, but especially this next election,” he said. Linda Brubaker. an associate editor at the Journal of the American Medical Association.

The New England Journal of Medicine similarly aimed to draw comparisons between the two sides on health issues, publishing a series of four articles in October on general health policy, health equity, health care affordability and insurance coverage.

Marcella Alsan, a health economist at Harvard’s Kennedy School who authored the paper covering health equity, said the goal was to cover epidemics that are uniquely widespread in the United States, with varying levels of prevalence linked to factors. such as race and socioeconomics. privilege: opioid overdose, gun deaths, childhood obesity and maternal mortality.

When compared to other high-income countries, “We’re kind of off the charts,” she said.

Benjamin Mason Meier, a professor of global health policy at the University of North Carolina, contributed two academic commentaries on the election. One, for Cambridge University Press, laid out the election stakes for his field; the other, for The Lancet Regional Health, made comparisons between the two candidates.

Rather than compiling information to compare the two candidates, his goal was to “develop nonpartisan teaching resources that can support classroom discussions on the global health impacts of this upcoming election,” he said.

Political, not partisan

Researchers who study science communication and perceptions of science say the decision to endorse a candidate risks further reinforcing the idea that science is a partisan issue.

“Science has always been political and will always be political,” Scheufele said. But partisan, he says, means “that we actually align our opinion with a party”.

Researchers have documented a decline in trust in science among conservatives since the 1970s, but the divide was exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic and subsequent debates over public health measures such as vaccines, quarantines and masking, experts said.

The Pew Research Center, which collects data on public trust in science and medicine each year, reported in 2022 that about 1 in 3 conservatives thought public health officials were doing a “good” or “excellent” job of responded to the coronavirus outbreak, and about half believed government officials overreacted to the pandemic.

“Before the Covid pandemic the gap between Republicans and Democrats was much more modest,” said Alec Tyson, an associate director of research at the Pew Research Center. In April 2020, 85% of Republicans said they had “excellent” or “fair” levels of trust in science; by December 2021, that number had dropped to 63%.

“That 22-point drop is the biggest change we’ve seen in this data in about a decade — and it corresponds pretty closely to the first year and a half of the pandemic,” Tyson said.

The growing partisan divide over science is troubling, Scheufele and others said, noting that scientists and health care workers are typically among the most trusted demographics in the country.

“The claim of the rightful place of science in society is that we are the best curators of knowledge and that we are so because we operate systematically, objectively and neutrally. That’s a claim that underlies everything we do,” Scheufele said.

If it is true that journal endorsements undermine trust in scientists more broadly, as the Nature Human Behavior study suggested, “they are undermining the capacity of the entire scientific community to talk about potentially policy-related issues,” he said. Cory Clark. , a behavioral scientist at the University of Pennsylvania who has studied why organizations make political statements. “Now we have an uphill battle when we’re trying to talk about our areas of expertise related to politics because the public doesn’t trust us, not because of what we did, but because of what these editors are doing. “

Americans’ trust in institutions, including the federal government, universities, and the media are also declining, and science is still held in relatively high regard. But that’s largely based on the idea that science is not a partisan issue, Scheufele said.

“The moment science becomes just an institution like any other that’s aligning itself with partisan views, we’re going to see exactly the same declines in trust,” Scheufele said. “For us, it’s existential.”